Democratizing the DBQ

What is a DBQ?

A Document-Based Question is an essay question, which requires students to use historical documents (both primary and secondary sources) to develop a thesis, requiring them to synthesize these sources. Sound difficult? It is. But I believe that all students can and need to develop high-level critical thinking skills. Students should learn history through investigating primary and secondary source documents from a variety of perspectives.

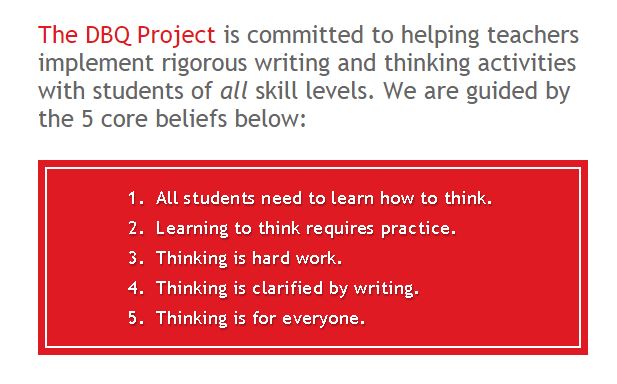

The DBQ Project

The DBQ Project provides units that engages students in historical inquiry and historical writing tasks. I use Mini-Q’s in my classroom because they use fewer documents (3-7 documents), and helps students understand the process of close analysis, interrogation of documents, argument writing, sourcing, contextualization, and corroboration of documents.

The DBQ Project provides units that engages students in historical inquiry and historical writing tasks. I use Mini-Q’s in my classroom because they use fewer documents (3-7 documents), and helps students understand the process of close analysis, interrogation of documents, argument writing, sourcing, contextualization, and corroboration of documents.

Another resource I use frequently in my Writing and Social Studies classroom, comes from Sam Wineburg and the Stanford History Education Group. The Reading Like a Historian curriculum also gives students practice in historical inquiry. For example, lessons center around a historical question and includes primary documents for analysis. Each lesson has three parts:

- Establish or review relevant historical background knowledge and post the central historical question.

- Students read documents, then answer guiding questions or complete a graphic organizer.

- Whole class (and small group) discussion about central historical question using documentary evidence to support claims.

Finally, The Zinn Education Project introduces students to a more “accurate, complex, and engaging understanding of United States history than if found in traditional textbooks and curricula” (Zinn Education Project). By giving students multiple perspectives, not just from those few individuals that are the most popular, but from individual people in history, I feel that I can help equip students with the analytical tools to make sense (and improve) today’s world.

I believe that this sort of critical historical inquiry can begin in social studies’ classrooms with fifth-grade students. In fact, research has been conducted using established theoretical frameworks for teaching historical thinking in elementary classrooms (Levstik & Barton, 2001). This type of “doing history” teaches students how to investigate primary source documents and how to begin interacting with multiple sources of information. Most recently, Avishag Reisman (2012) tested the effectiveness of using primary source instruction in history classrooms. The difference is that he used “Document-Based Lessons” designed by Stanford University’s History Education Group. This curriculum titled Reading Like a Historian (RLH) compiles “83 stand-alone lessons addressing the range of historical topics typically covered in an eleventh-grade history curriculum” (Reisman, 2012, p. 88). His study measured the effects of using RLH focusing specifically on: “(a) students’ historical thinking, (b) students’ ability to transfer their historical thinking strategies to contemporary problems, (c) students’ retention of factual knowledge about history, and (d) growth in students’ general reading comprehension skills” (Reisman, 2012, p. 87). This last goal, although subtle, offers teacher evidence that using primary documents in the history classroom, not only improves critical thinking skills, but reading comprehension as well.

References

American Council of Trustees and Alumni. (2012, August 11). What do college graduates know? American history literacy survey. Retrieved from http://www.goacta.org/publications/american_history_literacy_survey_2012

Barton, K. C. (2005). Primary Sources in History: Breaking Through the Myths. Phi Delta Kappan 86(10), 745-753.

Dewey, John. (1939). Intelligence in the modern world: John dewey’s philosophy. New York: Random House.

Hartzler-Miller, C. (2001). Making Sense of “Best Practice” in Teaching History. Theory and Research in Social Education 29(4), 672-695.

Hynd, C. (1999). Teaching students to think critically using multiple texts in history. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 42(6), 428–436.

Levstik, L. & Barton, K. (2001). Doing History-Investigating with Children in Elementary and Middle Schools. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

O’Connor, E. (2009). Teaching and using document-based questions for middle school. Portsmouth, NH: Teacher Idea Press. DOI: www.teacherideapress.com

Perfetti, C. A., Rouet, J., & Britt, M. A. (1999). Toward a theory of documents representation. In H. van Oostendorp & S. R. Goldman (Eds.), The construction of mental representations during reading (pp. 99 122). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Reisman, A. (2012). Reading like a historian: A document-based history curriculum intervention in urban high schools. Cognition and Instruction, 30(1), 86-112.

Rouet, J., Britt, A. M., Mason, R. A., & Perfetti, C. (1996). Using multiple sources of evidence to reason about history. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 478–493.

Stahl, S., Hynd, C., Britton, B., McNish, M., & Bosquet, D. (1996). What happens when students read multiple source documents in history? Reading Research Quarterly, 31(4), 430–456.

Wineburg, S. S. (1991a). Historical problem solving: A study of the cognitive processes used in the evaluation of documentary and pictorial evidence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(1), 73 87.

Wineburg, S. (1991b). On the reading of historical texts: Notes on the breach between school and academy. American Educational Research Journal, 28(3), 495–519.

Wineburg, S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Next Post

Next Post